Team SHARE hosted their first virtual symposium on 5th May 2021, chaired by Ms Sheila Gupta, Vice-Principal (People, Culture and Inclusion) Queen Mary University of London.

The symposium outlined the purpose of SHARE and each research theme. Talks were presented by Prof Chloe Orkin, Prof Jane Anderson, Dr Vanessa Apea, Dr John Thornhill, Dr Rageshri Dhairyawan and Ms Angelina Namiba (HIV Community Representative).

Watch the full symposium below.

Fast-Track Cities London and the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries hosted a joint webinar on Wednesday 23 June to mark 40 years since the first description of AIDS and explore the progress that has been made in treatment for HIV. The focus was on people and their experiences of AIDS and HIV.

We heard from people with HIV, doctors and nurses about treatment then and how it has evolved, what has been achieved so far and how looking after people has changed from a patient and clinical perspective. The panel also identified remaining challenges and actions needed so people get the best health outcomes, and what needs to happen next to reach London’s 2030 goal of “Getting to Zero”.

Speakers and panellists were:

Fast-Track Cities London is part of a global movement of cities to end HIV by 2030. The Mayor of London joined NHS England, London Councils and Public Health England to sign up to this commitment in 2018. It has brought together everyone working to end HIV with people living with HIV, the NHS, London’s Councils, doctors, nurses, public health experts and academics. It is the only place that brings everyone working in the HIV sector in London together. The roadmap to zero is a jointly designed action plan that shows the steps London will take to get to zero new cases of HIV, zero preventable deaths and zero stigma. Find out more here: www.fasttrackcities.london

The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries is the City of London Livery Company that represents doctors and pharmacists. The Society hosts the Diploma in HIV Medicine, which sets the professional standards for doctors involved in the care of people living with HIV. The Society has a particular interest in the history of medicine and pharmacy with its faculty of the History and Philosophy of Medicine. The Society is also a founder member of the Health Liveries group. Visit www.apothecaries.org to find out more.

On Tuesday 22 June 2021, National AIDS Trust hosted this online conversation exploring HIV and migration and the barriers faced by people born abroad living with HIV in the UK, chaired by Deborah Gold (Chief Executive at National AIDS Trust). Dr Rageshri Dhairyawan served as an advisor for this project and panellist at the virtual event.

Panellists are:

62% of all new HIV diagnoses in the UK in 2019 were among people born abroad. Half of these acquired HIV since moving to the UK. Despite this, there is currently no shared understanding of the policies and interventions needed to support people born abroad from acquiring HIV in the UK, and overcome barriers to testing and treatment for those living with HIV.

To end new transmissions of HIV by 2030, an accepted national commitment, we must make progress for all population groups, including those board abroad. National AIDS Trust wanted to understand the barriers they face when accessing HIV testing, treatment and care.

This event launched our latest report – HIV and migration, and shares our research findings and the recommendations we have made to improve the health outcomes and quality of life of those born abroad and living with, or at higher risk of, HIV.

The full report can be found here: www.nat.org.uk/publication/hiv-and-migration

The UK has passed the terrible milestone of 100,000 deaths with COVID-19. These losses have not been evenly spread throughout different communities. A disproportionate number of both severe cases and deaths have been among those from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds.

In England, analyses of data from the Office of National Statistics and National Health Service has revealed 2.5-fold to 4.3-fold greater COVID-19 mortality rates across a range of Black and South Asian ethnic groups compared with white groups.

As doctors working on the frontline of COVID-19 care, we wanted to understand the driving factors behind the differences in outcomes between ethnic groups within our community of East London, which was at the epicentre of the pandemic during the first wave. Our study included all of the 1,737 COVID-19 patients who were admitted to the five hospitals within Barts Health NHS Trust between January 1 and May 13 2020.

In contrast to many previous studies examining ethnicity and COVID-19 outcomes, we were also able to address how a range of factors including social and economic background, previous underlying conditions, lifestyle and demographic factors contributed to how patients fared.

In our sample, patients from Black, Asian and other minority ethnic backgrounds were significantly younger and less frail when they were admitted to hospital than white patients.

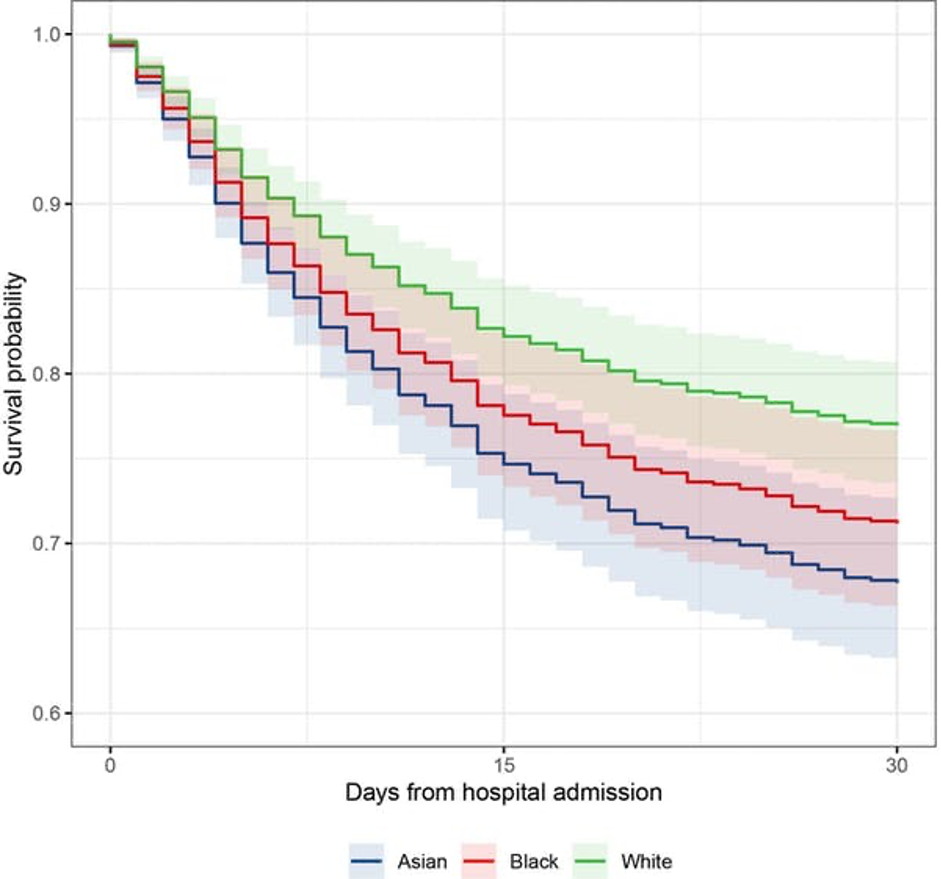

Black patients were 30% and Asian patients 49% more likely to die within 30 days of hospital admission compared to patients from white backgrounds of a similar age and baseline health. Black patients were also 80% and Asian patients 54% more likely to be admitted to intensive care and need invasive mechanical ventilation.

This graph shows predicted survival of Asian, Black and white ethnic groups to 30 days following hospital admission for a male patient aged 65. Probability of survival reduces as time passes but there are significant differences between Asian and Black compared to white patients, and these differences also increase over time.

When we accounted for the role of underlying health conditions, lifestyle, and demographic factors, the risk of death in Black and Asian populations did not drop to the same rates as white patients.

In our cohort, all ethnic groups experienced high levels of deprivation, however, worse deprivation was not associated with higher likelihood of mortality. This suggests ethnicity may affect outcomes independent of purely geographical and socioeconomic factors.

The risk factors associated with worse underlying health status are likely to be linked with wider social factors such as poor living conditions, being employed as a key worker and even language barriers that may get in the way of people adopting preventative measures to avoid getting sick. Structural racism also plays a role in generating and reinforcing inequities and must be acknowledged and addressed.

Although our study had a large number of patients, it was not possible to assess a more detailed ethnicity breakdown and so may not reflect the vast diversity that exists within ethnic categories (such as Bangladeshi, Pakistani, black African or black Caribbean). Future studies should focus on exposing specific inequalities that may exist between these sub-ethnic categories.

Similarly, we need bigger sample sizes to contextualise a number of potential factors including household composition, environmental concerns and occupation.

Although COVID-19 has placed ethnic inequalities in health outcomes in sharp focus, these differences have been widely documented for decades.

In another study, we are working directly with local residents in East London to understand their experiences both before and during the pandemic, so we can begin to find solutions together.

As the impact of COVID-19 persists, we continue to see significant numbers of Black, Asian, and minority ethnic patients admitted to our hospitals. The aftermath of this is yet to seen in its entirety as, in addition to the high rates of premature death suffered among these population groups, these frequently working-age patients will often leave hospital with long-term chronic health conditions, returning home with a greatly reduced quality of life.

We must respond now to the ethnic disparities that have been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic if we want to prevent them being inflicted on future generations.

Dr Yize Wan is a Clinical Lecturer in Intensive Care Medicine at Queen Mary University of London.

Dr Vanessa Apea is a Consultant Physician in Sexual Health and HIV Medicine at Queen Mary University of London.

News items relating to this story:

Evening Standard

As medical leaders, we are encouraged to think about our values. The Faculty of Medical Leadership and management standards for medical professionals are guided by values espoused in the Seven Principles of Public Life, which include integrity and accountability. But who and what we value is just as important as our personal values. And ideally, our espoused values should match our enacted values, so that what we do matches what we say we want to do.

With regards to the health outcomes of Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, despite our good intentions, there may be a gap between our espoused and enacted values. The health inequalities faced by these groups, which have been so conspicuously highlighted by COVID-19, existed well before this current pandemic and are present in many areas of health. Rageshri, list some examples on the full blog piece below, which make for uncomfortable reading.

Read full blog piece at: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjleader/2020/06/15/evaluating-values-by-rageshri-dhairyawan/

People from racial minorities are more likely to become very unwell or die from COVID-19 than those of white ethnicity. Compared to the general population, those of Black African heritage are 3.24 times more likely to die from COVID-19 and Bangladeshi populations are 2.41 times more likely to die.

38-year-old Nurul Islam from Forest Gate contracted the virus in February. He says: “I’ve never felt anything like it. One night I woke up suffocating. So many things came into my mind, I was scared and panicking. But what worried me most was my children – our 14-month-old daughter also contracted COVID-19 and was unwell”.

Now research will focus on East London, a densely urbanised, multi-ethnic area which has some of the UK’s highest incidence and death rates of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study will gain deep insight into the causes of COVID-19 based on the lived experience of East London’s racially diverse communities, through interviews and questionnaires. The researchers will work directly with local residents to understand their life before, and during, COVID-19.

The research will also address the lower vaccine uptake within racially minoritised groups. The team are already working with a number of boroughs on how trust around the vaccine can be built, and this study will help them to better understand and unpick the hesitancy within these groups.

The researchers are planning further studies into the treatment and outcomes of 3,000 patients from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds treated for COVID-19 at Barts Health NHS Trust, cross-referenced with local authority data from Tower Hamlets and Newham to explore factors like socioeconomic status, household density, and geographic health factors such as pollution.

It’s expected that the research will help the NHS and policymakers develop strategies to reduce the damaging impact of COVID-19 on Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities and could also provide useful insights for the many other health issues where ethnic differences exist.

The project is led by Professor Chloe Orkin, Professor of HIV Medicine at Queen Mary, and Dr Vanessa Apea, NIHR BME clinical co-leads for COVID-19. As clinical lead for COVID-19 Research for Barts Health NHS Trust, Professor Orkin has recently played a crucial role in setting up a COVID-19 vaccine trials centre at Bethnal Green Library.

Dr Apea, who was born in East London herself, says: “Poorer health outcomes in racially minoritised groups are not new, but have been revealed more starkly than ever by COVID-19, and must be urgently addressed. Authentic community engagement and co-creation of solutions are key to achieving health equity.”

Barts Charity funding for this study forms part of a suite of seed grants to help provide insight into a number of conditions affecting the health of East Londoners, including COVID-19.

Chief Executive of Barts Charity, Fiona Miller Smith, says: “As a charity dedicated to supporting the health of East Londoners, we are no strangers to the stark effects of health inequalities. And providing funding to better understand and ultimately overcome these inequalities is really important for us. As we are by no means out of the woods yet when it comes to COVID-19, we are rightly proud to be backing this very valuable contribution.”

Register your interest in taking part in the study at amplifyinglives.com

News items relating to this story:

Evening Standard